- Home

- Jeremy Josephs

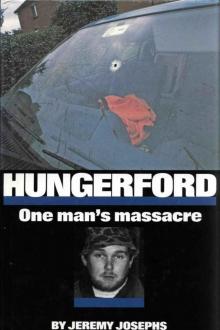

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre Page 5

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre Read online

Page 5

A sensitive man, PC Brereton would often try to allay his wife's fears. His standard light-hearted line was to the effect that should any maniac happen to strike in the vicinity, he would be the first person, and the fastest, running in the opposite direction. It didn't help a great deal, but just to address the family's worst fears could itself be therapeutic.

Roger Brereton began his police career as a bobby on the beat in Wantage, in Berkshire. The Breretons first lived with his parents, then hers. The new police constable would walk or cycle around his beat and soon developed a local reputation as a popular and friendly policeman.

'I was proud of him being a policeman. At least I could see him every day or night, according to which shift he was working. And I knew that once the initial training period at Hendon was out of the way, then there would be no more separations. He went on the driving course, passed it - and then waited for a posting. It was Newbury. When he passed the driving course, he was over the moon - you couldn't get his head through the door. And I do remember thinking when he became a traffic cop, thank God for that - now he'll only be dealing with TAs - traffic accidents, that is. That now he would be safe.'

Brereton loved his work. His childhood dream had come true. There were indeed lots of chases, accidents and 'domestics'. The work was always interesting and varied. Seldom was there a shortage of compelling anecdotal material to retail to Liz. For policing purposes Brereton's Newbury traffic base had within its jurisdiction the town of Hungerford. The two towns also had other links, for radio communication at Hungerford was by way of personal UHF radios operated from Newbury, and Hungerford was in any case part of the Newbury Sub-Division, and its personal radios were controlled by the Newbury Control Room.

Professionally, Brereton had little to do with Hungerford, however. When the Breretons set foot in the town it was more likely to be for pleasure than police duties, for both were very fond of the place. A favourite treat was to picnic on the Common, or to browse around the parade of antique shops, second to none in the area. Only ten miles from their police house just outside Newbury, for them Hungerford was the ideal outing.

Roger Brereton was certainly a friendly man, but he could also be tough. How else could he have broken up a pub brawl in which knives were used, as he had once had to do? But he was aware that as far as the implementation of the Road Traffic Act was concerned, sometimes a severe dressing-down could be just as effective as an endorsement or a fine. He once decided to adopt such an approach with a motorist who was driving at well over the speed limit on the M4. As he launched into his reprimand Brereton could not understand why the motorist was not suitably humbled, or what might account for a smirk on his face. Being caught by the police driving at over eighty miles per hour on one of Britain's main motorways was surely no laughing matter. Brereton had failed to remove some Christmas decorations from his policeman's hat after the annual office party, and it was the juxtaposition of tinsel and a ticking off which had proved so comic. Always keeping a keen eye on those with designs on the speed limit, Brereton had also once stopped a member of the Royal family for this same offence.

On the morning of 19 August 1987 the sun was shining and there was a gentle breeze in the air. At eight o'clock Roger Brereton set off for work. Liz was showering when he rushed in to kiss her goodbye. Both had overslept and there had been a rather unseemly rush for the bathroom.

'It wasn't much of a kiss really,' Liz explains. 'His glasses steamed up as he popped his head round the curtain. I reminded him that he had forgotten to wash his hair, because he always liked to look his best for work. As he rushed down the stairs he shouted out: "Not to worry, I'll do it tonight. See you later.'"

Liz topped up the family income by working as a home help. She would tidy the homes of the elderly and infirm, cheering them up in the process. Because a police career is so finely structured, both in terms of age limits and pension rights, many personnel and their families begin to address the issue of retirement relatively early. Roger Brereton was no exception. He always liked to think ahead. In his own mind, at least, his agenda was very nearly fixed. He would in time buy a pub and retire to the West Country. Roger and Liz would run it jointly, and for both it was a very appealing prospect. Occasionally, as Liz went about her work, she would permit her mind to embroider this scenario. Every time, she liked very much what she saw.

But that Wednesday has stayed in her mind for a very different reason, as she explains: 'Normally, when I used to go on my rounds as a home help, most of the houses I went to would have their radios or televisions on. But on that Wednesday none of them did. When I got to my last lady, it was ten to one in the afternoon, and I could hear the sound of police sirens. I knew I would hear all about it later that evening when Roger would get in from work. I thought it was probably a bad TA. In fact I can remember my exact words to that lady: "Some poor bugger's in trouble," I said.'

FIVE

'Something about that Michael Ryan'

If, on that sunny August morning in 1987 when Sue Godfrey and her children were picnicking in the Savernake Forest, Michael Ryan was behaving strangely near by, so too had he been doing at home. Towards the end of July he had become involved in a row with Mrs Christine Reagan, a neighbour whose children had been irritating him by playing on his drive. Ryan's remedy for any such minor trespasses was to fire airgun pellets at his neighbour while she was hanging out her washing. A little earlier in the year he had also crossed swords, almost literally, with another neighbour, Ivor Pask, on whom he had threatened to draw a knife after an argument prompted by the constant fouling of the footpath by Ryan's dog. Others within the vicinity had come to fear Ryan too, most notably the children of South View, who had long been terrified by his style of driving as he roared off on his solitary evening excursions in his sporty Vauxhall. Justin Mildenhall recalls: 'He was mad in his car. Our alley's so narrow, there's no footpath. So if a person in a car comes up and there's someone in the lane, they normally slow past on the bank. But Michael, he'd just go up there really fast, and you would have to press yourself against the hedge or be run down.'

While Ryan was sporadically terrorizing his neighbours, a tragedy was unfolding on the other side of the globe. For on 9 August 1987 the quiet of a Melbourne suburb was shattered by a young man named Julian Knight, a nineteen-year-old failed army officer cadet. He had kitted himself out in paramilitary gear and armed himself with two semi-automatic rifles and a shotgun. He then stalked passers-by from behind bushes, picking them off one by one. In this way he casually murdered six people and wounded a further eighteen. The drunken gunman was finally caught by a wounded traffic policeman, but only after he had run out of ammunition.

But why should a person explode in such a destructive and murderous fashion? For decades psychiatrists have struggled to provide compelling explanations. And yet the personalities of inexplicably violent offenders have been documented nonetheless. For, as long ago as 1963, a group of doctors published a paper entitled The Sudden Murderer, which can be found in Britain's Archives of General Psychiatry.

'Such a murderer,' they argued, 'was likely to be a young adult male, with no history of previous serious aggressive anti-social acts, who had been reared by a dominant natural mother in a family of origin that had been overtly cohesive during the patient's childhood. The father had either been hostile, rejecting, overstrict or indifferent.'

Building on this research, Jack Levin, Professor of Sociology at Northeastern University, Boston, has been able to construct a model for the type of person who, like the gunman Julian Knight, kills indiscriminately. There is a combination, according to Levin, of frustration, a precipitating event such as unemployment or divorce and, most important of all, access to and training in firearms.

The problem with such a model, however, is that large numbers of people can fall within its scope. Certainly many millions of people are frustrated with various aspects of their lives. Millions divorce. Millions are unemployed. And certainly large numbers o

f people have both access to and training in firearms.

There was indeed something distinctly odd about the behaviour of Michael Ryan; a good many of the people of Hungerford could have testified to that. Furthermore, he fitted Levin's model. But then so did many other members of the Tunnel Rifle and Pistol Club. And when Peter Browning, then a thirty-five-year-old Royal Marine, met Ryan at the Devizes club on the afternoon of Tuesday 18 August, nine days after the carnage inflicted in Australia, he was quite unaware of the slightest trace of abnormal behaviour: 'I remember that he was wearing brown paramilitary boots, a pair of plain green denim fatigue trousers, a green woolly jumper and a shooting duvet jacket. To me he looked like a regular gun-club member. He was really very polite. Just a nice pleasant lad who liked to talk to people about guns.'

A number of Ryan's neighbours from South View knew otherwise; so did various colleagues from his last foray into the world of work. But ask them to be more specific and they would be at a loss to identify with any precision what it was about Michael Ryan that set him apart from the rest. Even Ethel Stockwell, a retired nurse and a close friend of Dorothy Ryan, never fathomed Ryan's personality: T don't know what it was about that young man. He was impenetrable. But there was definitely something about him. Yes, there was definitely something about that Michael Ryan. And yet I could never quite manage to put my finger on what it was.'

SIX

Tactical Decisions

There was nothing strange about Paul Brightwell. His ' career had followed a conventional enough path. He had joined the Thames Valley Police in 1970, and served at a number of its centres, including Aylesbury, Slough and High Wycombe. For many years he had worked in the Traffic Department. But with a view to advancing his career and adding spice to his daily routine, he eventually applied to join the Support Group, whose officers constitute the Tactical Firearms Team.

T was in the Support Group between 1979 and 1985,' Bright-well explains, 'when I was promoted to the rank of Sergeant. I then left for a couple of years - only to return to the group as a Sergeant at the beginning of 1987. I was then thirty-five years old. When I married Sandy I was already in the job, so she had a fair idea of the sort of work I would be involved in and she has always backed me all the way. I do enjoy our rather specialized field of work. Mind you, I also find the whole area of firearms rather difficult. Because, unlike many people in the group, I'm not a natural shot -just a good average - so I really do have to work at it.'

The first Thames Valley Police Support Group began operations in 1969 on an experimental basis under the command of the Assistant Chief Constable. It consisted of twenty-seven selected officers and dog handlers. The object of the Group was to provide a highly mobile unit of officers, able to perform a preventative role, to support divisions in most aspects of police work and, perhaps most important of all, to give immediate assistance after a report of a serious crime.

In its early days the Group was most active in and around Aylesbury, Amersham, Slough, Bracknell and Reading - familiar terrain to Sergeant Brightwell - where crime was rife. But it also assisted both in large-scale enquiries and local events such as the Henley Regatta and Royal Ascot.

By 1970 an independent streamlined unit was in place, with a remit covering the whole of the Thames Valley police area. As the years went by, so the Support Group grew in both stature and reputation. Nonetheless it still retains its initial role, continuing to deal with a variety of incidents, such as the policing of major events, crime investigations, house-to-house enquiries, searches and preventative patrols in response to terrorist threats.

The major function of the Support Group, however, is that its officers form the Thames Valley Police's Tactical Firearms Team, and this has always been the cornerstone of its role. The Team is specifically trained to conclude armed incidents, whether confronting a gunman on the loose or attempting to conclude a siege. It is a highly trained and heavily armed specialist squad whose overriding duty is to provide an efficient, disciplined, twenty-four-hour response to any shooting incident within its police area. Considerable skill and experience are required of candidates for the Group, and every officer selected is trained to a high degree in both tactical and shooting skills.

The Support Group now consists of forty-eight officers headed by a Chief Inspector. There are two Inspectors, one with responsibility for the north of the police area, the other mandated to cover the south. Under each Inspector there are two parties of ten constables and a sergeant working alternate day and night shifts, with one constable acting as coordinator. The precise nature of the work of the Support Group remains shrouded in secrecy, and it uses unmarked vehicles, although these are equipped with portable blue lights and two-tone horns or sirens.

During the summer of 1987 the head of the Support Group was Chief Inspector Glyn Lambert. Having had an operational career within the Thames Valley Police, he had been selected first as an Inspector in the Support Group, before going on to head it. Chief Inspector Lambert describes his role and the work of the Group thus: 'Of course I have passed all the necessary firearms courses myself. But you need to be more than just a proficient shot: you must be able to think and to train tactically. You have to learn how to move around and to be sensible in your approach. Whenever a major firearms incident occurs within our jurisdiction, overall control actually falls to the Assistant Chief Constable. But because of my advisory role as the tactical firearms officer my role is also quite crucial, with my advice being sought on the firearms issue. Once notified of an incident I will ensure that our firearms package gets rolling - that is to say, the communications package, tactical dogs, weapons, officers, helicopters and whatever else I think might be helpful and relevant for the operation. Of course we do have powerful rifles in our pack, although I have to say that the Kalashnikov is a hell of a weapon. That's because it's self-loading. Once launched, its bullets travel at 2900 feet per second - and they can cover a distance of up to four miles. And because of its high penetration, it really is a most fearsome weapon.'

Chief Inspector Lambert indeed had a highly trained group of men, but he did not have the most modern equipment. For example, the control room at the force's headquarters at Kidlington had out-of-date communications equipment. Nor at that time did the Thames Valley Police then have their own armoured Land Rovers. At the time of the Hungerford massacre, these were a new thing for the police. While the Metropolitan Police had some, few other forces did, and in any case they were not often needed. Compared with some forces in the country, however, the Thames Valley Police were privileged, as Chief Inspector Lambert explains:

'In 1987 there were only four police helicopters in the country. And we were fortunate enough to have one at our disposal. I always have great faith in the helicopter and I like to work closely with it because it really is an excellent spotting tool. On Wednesday 19 August, however, it is true to say that our helicopter had been temporarily grounded for repairs.'

While repairs were being carried out on the helicopter, the officers of the Support Group were at Otmoor, an army training range, where they had gone to meet the Firearms Training Unit. Sergeant Paul Brightwell was there on that day, and recalls: 'That Wednesday had been allocated as a firearms training day at Otmoor, which is about eight miles north of Kidlington HQ and therefore not so far from Oxford. Every month we would have at least one or two training days. I used to enjoy them very much. On other occasions there would also be tactical training - how to deploy at different incidents and so on. Being an outdoor range, Otmoor was glorious on that sunny Wednesday morning. We spent the first few hours in straightforward firearms training.'

Sergeant Brightwell and his colleagues at the training range were the only officers from the Support Group on duty that day. The rest of the team were off duty, or just about to come on. Thus there was no tactical firearms cover in the south of the Thames Valley police area at all. In policing terms, however, there is nothing remarkable about such a lack of cover, as the former policeman and firear

ms expert Colin Greenwood explains: 'Some people believe that you'll never be able to get a tactical unit into action quickly enough; that effective response times can only be achieved when weapons become available to many more local officers. When I was with the police we used to do tests. I would go back and pick a day - three o'clock in the morning on 4 August, say - and then demand of the Force how many armed men would have been available. And each time that was done, we were frightened by the result.'

The Government's reluctance to allow the police ready access to firearms can be traced back to the first half of the 1980s. For it was then that the police had made a series of disastrous mistakes with their weaponry. An innocent man, Stephen Waldorf, had been gunned down in his car in 1983, and then, two years later, Mrs Cherry Groce was crippled by police fire in Brixton. Only a few months later a five-year-old boy, John Shorthouse, was shot by a policeman in Birmingham. There was a huge public outcry and the seeds of a new approach were sewn. Political pressures resulted in the Home Office issuing a directive that considerably more caution should be shown in the handling of firearms. As a result, the rank necessary to sanction an armed operation was increased from inspector to the Assistant Chief Constable himself. The key to increased public safety, a Government working party later argued, was to have fewer firearms officers, more professionally trained.

Despite this new caution by the Home Office, by 1987 more than 14,000 British police officers were authorized to use guns. The prevailing legislation was then the Criminal Law Act of 1967. Sergeant Brightwell explains: 'We all used to have to carry a "white card" which showed our authority to use a firearm and which laid out the guidelines under which we could operate. The card quoted from the '67 Act, saying that guns can be issued when "there is reason to believe that a police officer may have to face a person who is armed or otherwise so dangerous that he could not safely be restrained without the use of firearms".'

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre