- Home

- Jeremy Josephs

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre Page 2

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre Read online

Page 2

Hungerford is rich in tradition. Indeed, many of its traditions are entirely incomprehensible to people from outside the town. This is never more true than on Tutti Day, always held on the Tuesday of the second week after Easter. On Tutti Day the whole of Hungerford goes to town.

'Some people say Tutti Day is all a lot of nonsense,' declares Ron Tarry. 'That it's just an excuse for a big booze-up. But these are an important part of Hungerford's traditions. Because if it wasn't for the work that people had put in in the past to keep their commoners' rights, they simply wouldn't be there now. The Common is now there for everyone to use. And the fishing rights on the Kennet are reserved for commoners or anyone who rents them from the Town and Manor. Tutti Day is the day when the commoners elect all these obscure officials, like our two Ale-testers, whose job is to ensure that the ales are a goodly brew. I enjoy all of these traditions. They are unusual, and very much part of our history. They make Hungerford all the more special.'

Ron Tarry is right. Tutti Day is certainly unusual. For nowhere else in England are you likely to find two Tithing men, or 'Tutti men', resplendent in morning dress, with beautiful long staves, their Tutti poles topped by an ingenious arrangement of spring flowers and streamers of blue ribbon, being sent on their way by the Constable. And the Constable's orders to his two smart Tutti men? To visit all the commoners' houses to demand a penny and a kiss from all the ladies, even if that means climbing ladders to windows when normal ingress is denied. Maidens are kissed; pennies and oranges thrown to the children.

And so the proceedings continue throughout the day, as they have done throughout the centuries. The Tithing men duly dispatched, the Constable takes the chair at the Manorial Court and the day's activities begin. These include the Hocktide Lunch, which is followed by another Hungerford speciality, 'shoeing the Colts'.

'I haven't really been all that much involved in Tutti Day and the Hocktide Lunch,' Ron explains, 'because these have always been organized by the Town and Manor of Hungerford, whereas my involvement has been more by way of the town council. But I have been invited to the Hocktide Lunch. It's a marvellous occasion. The people attending this lunch for the first time are known as Colts. These people are caught and shoed by the blacksmith, whose solemn duty it is to drive a nail into the sole of the shoe of that person until a cry of "Punch" is heard. When they do this, they then have to pay for a bowl of punch. It really is a lot of fun.'

The term 'Tutti' is derived from the West Country name for a nosegay or a flower - a tutty. With its obscure and ancient rituals, Tutti Day comes but once a year. For the remaining 364 days Hungerford is as it has been since time immemorial. A former resident of the town recalls his childhood thus: 'Of all the quiet, uneventful places in my 1950s childhood, Hungerford was the quietest. I remember those utterly motionless summer afternoons in the High Street. My grandmother and I would get off the coach from London at the Bear Hotel and carry our cases, stopping frequently for rests, up the broad main street, with its red-brick clocktower. Invariably, the town clock would be tolling its slow, flat note, assuring us that, whatever might be happening elsewhere in the world, nothing ever happened in Hungerford.'

In fact something did once happen in Hungerford. For on one of the back roads leading out of the town towards Lambourn there is a monument that few notice. Half-buried in the hedgerow, it commemorates two policemen murdered there by a gang of robbers. But that was back in the 1870s, ironically just a few years after the opening of the town's small but proud police station. The former resident was right, though, for ever since that time nothing extraordinary had happened in Hungerford.

For Ron Tarry, Wednesday 19 August 1987 was a typical working day. He was out and about in his maroon Ford Escort estate, working for his employer, an agricultural cooperative. Ron's task was the same as ever: to sell stock feed, seed, fertilizer and other agricultural products to the farmers of Berkshire.

'I remember that day well,' says Ron. The sun was shining. The windows were down. I was driving around the Lambourn Downs, listening to the radio. I was just north of Lambourn at a place called Seven Barrows, and preparing for my next call. Then I heard the early-afternoon news.'

THREE

'That shows the power a gun gives you'

Michael Robert Ryan was born at Savernake Hospital on 18 May 1960. His father could hardly get to the registration office quickly enough, and Michael's birth was duly registered in less than twenty-four hours. The reasons for this haste were twofold. First, as a white-collar council employee, he knew all about the inner workings of a small local bureaucracy. Secondly, and more importantly, in his mid-fifties Alfred Henry Ryan was delighted to have finally fathered a child. The prompt issue of a birth certificate provided confirmation that Michael Ryan had made his belated entry into the world.

I remember the day when Dorothy returned from the hospital with Michael as a baby,' recalls the Ryans' neighbour Guytha Hunt. 'I was thrilled to bits. I saw him grow up from the very beginning. She doted on him - that's the word. I sometimes used to say, jokily so as not to offend, that I wouldn't get him this or that. That I wouldn't jump to it when he clicked his fingers. But she loved him as a son and that was it. There was nothing you could do. It just wasn't up to neighbours like me to interfere. So we didn't.'

Alfred doted on his son too. He was the Clerk of Works for Hungerford Rural District Council, and had a rather unflattering reputation in the area as a perfectionist who enforced strict standards of behaviour. But since he was already approaching retirement when his son was born, he was happy for his wife to take charge of the boy's upbringing. Dorothy, over twenty years younger than her husband, loved her son very much indeed. T just don't know what I would do if anything ever happened to Michael,' she would often muse. And the hallmark of Dorothy Ryan's brand of loving was indulgence. Not surprisingly, it did not take young Michael too long to realize that his wishes were usually likely to be fulfilled. Soon the formula had been set: what Michael wanted, Dorothy provided. He became the boy who was given everything: toys and train sets, records and clothes, bikes and, later, cars.

Unlike both her husband and son, however, Dorothy was a well-known figure in Hungerford, and highly respected too. The general manager of the Elcot Park Hotel, where she worked as a part-time waitress for twelve years, remembers his former employee as extremely popular, conscientious and hard-working -'a real salt-of-the-earth figure'. So popular was Dorothy that when, shortly before the summer of 1987, she finally passed her driving test at the twelfth attempt, at the age of sixty-one, the hotel's management presented her with a bottle of champagne, a gesture of admiration for her gritty determination. However, the most constant beneficiary of any additional income generated by Dorothy's dedicated efforts was not herself but her son.

As a young child Michael Ryan developed a particular attachment to Action Man, the commando-style plastic doll beloved of so many boys at that time. True to form, Dorothy saw to it that Michael's Action Man was exceptionally well kitted out, with several different uniforms and virtually every accessory on the market. For this was what Michael had wanted.

'He was moody and self-centred,' his uncle, Stephen Fairbrass, would later recall, 'but that did not mean that it was impossible to like him.' It might not have been impossible, but few did. And when it came to his schooling, Ryan was himself certainly no junior Action Man. Quite the contrary, in fact. He attended the local primary school, just opposite his home in South View, before moving to the John O'Gaunt School. He was a C-stream pupil of below-average ability, as a former classmate recalls: 'He was in a remedial class or in one of the lower sets at secondary school. We used to try to get him to join in games, but he appeared to be moody and sulky, so eventually the other children would just leave him alone. The only person I ever remember seeing him with was his mother, who adopted a very protective attitude towards him.'

As an eleven-year-old, Ryan was photographed along with all the other schoolchildren. Despite the best efforts of the local

photographer, even on that occasion he was unable to manage a smile for the camera; indeed it is not difficult to detect a fearful expression on his face. From the very earliest of days, Michael Ryan was a child apart.

Guytha Hunt recalls that throughout Ryan's primary-school days she saw little evidence of children coming to and going from his house at South View: 'In fact I never once saw any friend come to play with him throughout those early years. Actually I had a lot of time for Michael, but no one seemed to have a lot of time for him -apart from his parents, that is.'

He might not have been seen by Guytha Hunt, but there was eventually one boy, Brian Meikle, who did come to play. He and Ryan were best friends at school, although they eventually grew apart when Brian married in 1980. But during their school years, they were two of a kind, enjoying motorbike scrambling, and both well aware that neither of them was destined to scale the heights of academia. Brian explains: 'Neither of us was very good at school. In the fifth year, when Michael was in a remedial class for one subject, he used to play truant a lot. The other lads used to pick on him -because he was small - but he didn't get himself into fights because he just wouldn't have been able to stick up for himself. He was certainly no Rambo - more of a Bambi really.'

Brian Meikle was right. His friend was frequently a victim of bullying at school. Other children detected his sense of isolation and preyed on it without mercy. And throughout his long, lonely persecution, Ryan would say nothing, preferring to simply take the punishment, always remaining silent and still. His former friend and classmate remembers it well: 'It was quite sad really, because he would always sit on his own. He never did anything to harm anybody. He wasn't popular either with the boys or girls though. He took a lot of stick - and it just made him even more withdrawn. He retreated into his guns, and they became his only real friends.'

Nor did Ryan shine in sport. His former physical education teacher, Vic Lardner, remembers only a sullen and shy boy: 'He was quiet, withdrawn you might even say. He certainly wasn't too keen on sports, because it was difficult to get him to take part at all.'

Not surprisingly, Michael Ryan wanted out. The troubled teenager's conclusion could hardly have been more clear: the sooner he was free of the confines of the John O'Gaunt School, the better his world would be. His father, however, was not so eager for him to leave school so soon after his sixteenth birthday, and without a single examination pass under his belt. In the Ryan household a conflict developed as to when and what Michael's next move should be. But when his son promised to enrol at the Newbury College of Further Education, Alfred Ryan relented. Perhaps there, he thought, Michael would receive a more appropriate and vocational type of training.

Having taken his place on the year-long City and Guilds Foundation Course, Ryan seemed at first to have found a home for himself. It was a new and challenging environment. But within a few months a familiar pattern had begun to emerge. For during his time at Newbury College Ryan remained uncommunicative, always attempting to make himself as inconspicuous as possible by sitting near the back of the class. Like many others with whom Ryan came into contact, course tutor Robin Tubb can recall only a shy, repressed personality: 'He was an exceedingly quiet student. He needed a lot of encouragement. He did pay attention though - he was a real trier. It was just that he wasn't very good. I got the feeling that he was frustrated with his inadequacy. He wanted to do well, but he was very timid. If you showed him how to use a chisel, you would have to say: "Now hit it." '

A timid and withdrawn loner, however, was far from the image Michael Ryan was eager to project to the world. For his pattern of behaviour made it clear that his aim was to be taken as something of an Action Man himself. But a new persona had first to be concocted. He invested in a military camouflage jacket, which, to his mind, lent authority to his idle boast that he was once a member of the 2nd Parachute Regiment. And whether in Hungerford or elsewhere, he would always do his best to walk upright like a soldier, chin up and chest out. Neighbour Victor Noon remembers his antics well: 'Michael was into buying and selling old military swords and he once owned a tommy gun. He was a bit of a military freak and always wore combat gear. He would tend to his guns the way most people would tend to their plants.'

Ryan's shed might have housed a considerable arsenal. He might well have strained to walk upright like a soldier. His patter to the world might have sounded completely plausible. But such boasting and behaviour belonged only to the private world of his imagination. In fact, for Ryan, reality and fantasy were almost equal and exact opposites, as another Hungerfordian, Denis Morley, explains: 'I worked with Ryan together on a project at Littlecote. He was employed as a general labourer there. I thought he was a wimp. He was very much a mummy's boy. She bought him the best motorbike when he was old enough to have a licence. And then he started going round in a posh Ford Escort XR3i. His latest acquisition was a flashy new Vauxhall Astra GTE. He would always have the latest registration plate too. But he certainly wasn't the sort to get involved in a punch-up. In fact he wouldn't even go up a ladder at Littlecote.'

For Ryan, ladders clearly represented an unacceptable risk. And yet he was deeply fascinated by the worlds of survivalism and combat, where the stakes are considerably higher. As a result he was a regular visitor to the Savernake Forest, where several survival huts can be found. Most of these are made from branches broken and woven around a tree in order to blend with the background of the forest. The forest is entrancing, with tangles of pine, beech and oak criss-crossing a network of unmarked lanes, and in season, red puffs of poppies amid the fields of brown, ripening corn which break up the woodland. But Ryan's repeated visits to Savernake were entirely unrelated to the natural beauty of the environment, as Charles Armor, with whom Ryan worked briefly, recalls: 'He used to spend quite a lot of time in Savernake pretending to be on manoeuvres. He used to tell us, when we worked together at Littlecote, that he would camouflage himself and creep up on picnickers without them knowing. He would watch them for a while - and then disappear.'

'He were a right nutter, were Michael Ryan. I can remember running around the garden when I was about six years old, some twenty years ago, because he used to use us as moving targets for his air rifle.'

Wynn Pask was right. Ryan had terrorized his younger neighbour for some time. And a good many of Wynn's friends too.

'He never hit us but it was always very frightening,' Wynn recalls. 'Even when he was just thirteen years old, he would lean out of his bedroom window, which looked on to our garden, and take shots at us with his air rifle. It was the same thing when we were playing - he would come out with his air rifle. We did complain about it, but not all that much really because we were too scared of him at the time. I often saw him going out into nearby fields and on to the Common with a shotgun when he was just a kid. He even used to take aim at his father's cows, which were kept behind his house. He would shoot at anything, would Ryan. A right bloody lunatic'

Fourteen years later, Michael Ryan remained gun mad. If anything, his devotion to the world of arms had increased with the years. It was his mother who had initiated him by presenting him with his first gun, an air pistol. Dorothy Ryan was constantly lavishing gifts on Michael, her only child, and the air pistol was followed by a moped, then a scrambler motorbike and, later, a string of smart new cars.

There is nothing to suggest that these later offerings were not appreciated. Yet Michael Ryan savoured nothing so much as the acquisition of a new gun. Whereas supporting the local football club was something of an interest, collecting guns soon became a passion. And wherever Ryan went, his gun went too - even if it was just to the local pub for a pint.

Throughout his teenage years and later, Ryan spent long hours tucked away in his garden shed, which soon housed a small arsenal. Every now and then he would emerge to fire at a tin can on the garden fence or take a shot at a bird. The sound of Ryan firing off rounds both behind his parents' house, 4 South View, and in the general vicinity of Hungerford, became quite commo

n.

And then it was back to the garden shed to grease, oil, polish or strip his formidable array of weaponry. Sometimes Ryan's visits to the shed would have no precise purpose, the hours being whiled away simply admiring his treasured collection. Given the opportunity, he could hold forth on every aspect of his hobby for hours, while secreted in his bedroom was a comprehensive range of literature on guns, with books, reviews and survival magazines packing every inch of available space.

Ryan's passion for weaponry singularly failed to impress the next-door neighbours. Just as the Pask family had suffered, so too had the Hunts, who for over twenty years had lived immediately next door to the Ryans at 5 South View. Mrs Hunt remembers Ryan's antics well: 'My husband often used to see Michael coming out the house with his guns, place them in the boot of his car and then cover them with blankets. My husband would say, "I wonder where he is off to with those guns." My husband used to keep geese and chickens. And of course Michael was always around and about with his airgun - and I remember my husband saying, "Michael, if you kill one of my birds, woe betide you." He would also go to his bedroom window and shoot the birds in the trees with his guns, and this also upset my husband.'

By the summer of 1987 Ryan's collection of weapons consisted of two rifles and three handguns. They were his pride and joy, something about which he could boast to relatives and acquaintances alike. Nor was there anything illegal in this arsenal kept in the Ryans' brick-built, end-of-terrace council house. On the contrary, Ryan had held a shotgun licence since 1978. As his collection had expanded to include other firearms, so his licence had been amended accordingly, as required by law. The Thames Valley Police had, in the twelve months before August 1987, vetted the young gun enthusiast on at least three occasions, once in November 1986 and twice in early 1987. As the storage facilities were found to be in order, there was no good reason for the relevant authorization to be withheld, and it was not.

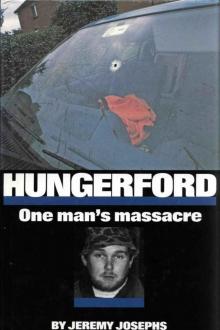

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre