- Home

- Jeremy Josephs

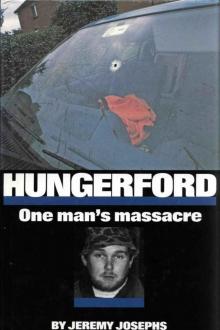

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre Page 3

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre Read online

Page 3

Under the terms of his firearms certificate Ryan was entitled to own five guns. It was his constant chopping and changing of his weaponry which had prompted the police visits. Constable Ronald Hoyes, the Hungerford community beat officer, was one such official visitor to the Ryan household. He explains: 'Having worked in Hungerford for thirteen years, I had had no previous dealings with Ryan at all and I knew that he had never been in any trouble with the police, apart from one single speeding offence. He appeared to me to be a fit and responsible person to hold a firearms certificate.'

PC Hoyes's visit was required because Ryan had again applied for a variation to his certificate in order to include a Smith and Wesson, a .38 pistol, for target shooting. The amendment came through without undue delay. Everything was in accordance with the law.

Another police constable, Trevor Wainwright, also a member of the Hungerford constabulary, took the same view as his colleague on his visits to 4 South View. In fact he lived just around the corner in Macklin Close. These judgements were supported by Ryan's own doctor, Dr Hugh Pihlens, whose name had been associated with Ryan's original application. Again, both PC and GP found Ryan to be sane and safe. Additional legal requirements were duly fulfilled by the purchase and installation of a Chubb steel cabinet, which was then bolted to Ryan's bedroom wall. But in reality the licensee kept the guns and hundreds of rounds of ammunition in the garden shed, a flimsy structure which had long been the nerve centre of Ryan's quasi-military operations, as many neighbours knew.

'Michael was always fascinated by guns,' his aunt, Constance Ryan, confirms. 'It seemed to me as if he felt more important and powerful because of them - perhaps because he wasn't all that big himself, I don't really know. But I do remember Michael telling me that once he had met a person while out rabbit shooting and this person had started getting saucy. Michael pulled a revolver out of his pocket and pointed it at the man, and then watched with satisfaction as he ran off. I remember the lesson he drew from this incident very clearly. "That," he said, "shows the power a gun gives you, Auntie.'"

Michael Ryan's fixation with weaponry might have made him something of an exception in Hungerford. But he was by no means unusual in terms of the country as a whole. For in the summer of 1987 Britain's gun culture was very widespread indeed. Ryan was just one among 160,000 licensed holders of firearms and 840,000 licensed holders of shotguns. However, the number of shotguns in legitimate circulation at that time was estimated at around three times that number, because several could be held on a single licence. And according to an estimate published in the Police Review there were then possibly as many as four million illegally held guns in the country. Gun shops and gun centres were also widespread, with more than two thousand legitimate dealers trading in arms, many extremely successfully, and some eight thousand gun clubs where the enthusiast could hone his skills.

In his love for guns, then, Michael Ryan was not alone. So when he applied to join the Dunmore Shooting Centre at Abingdon in Oxfordshire in September 1986, there was nothing particularly remarkable in his application. For Ryan membership of the Dun-more club was particularly attractive because it incorporated what it claimed was one of the biggest gun shops in the country. Ryan proved to be a good customer, spending £391.50 on a Beretta pistol shortly before Christmas 1986, and then buying a Smith and Wesson for £325, a Browning shotgun, a Bernadelli pistol and two other shotguns during the following year. Ryan borrowed the money to finance these transactions, a Reading finance company handling his repeated applications for funds.

There was more besides to attract the young gun enthusiast, for the Dunmore Centre's shooting gallery had a 25-metre, full-board, seven-lane range with television-monitored targets. The Centre, situated not far from Ryan's home, also had a turning-target system, enabling him to practice rapid fire and combat exercises, an area of gun expertise known as practical shooting. Here, accuracy is tested not on Bisley-style targets where closeness to the bull's-eye gains the most marks, but under simulated combat conditions, firing at representational figures, usually life-sized depictions of terrorists. The aim here is to kill or maim the 'enemy'. In the summer of 1987 there were no fewer than forty survival schools' scattered around Britain, and magazines like Desert Eagle, Combat and Survival, Soldier of Fortune and Survival Weaponry were then enjoying a rapidly rising circulation. Michael Ryan was simply one of the gun-loving crowd.

Or was he? Certainly there was something which did not quite ring true. For Ryan's extensive range of macho trappings should surely have made him the envy of the neighbourhood. One might have expected a string of callers at 4 South View: youngsters anxious to sit in his high-performance car or interested in his impressive armoury. Yet not only was there no waiting list of prospective visitors anxious to inspect Ryan's collection; there was nobody in Hungerford remotely interested in Ryan or his weapons. For the reality was that Michael Ryan's personality simply did not match his image. One of his former workmates, John Mitchell, explains: In no way was he ordinary. He had a quiet intensity about him, which nobody really liked. Sometimes he was very pally, but you could tell that the rest of the blokes were not having any of it. He used to talk about how fast he used to drive here, there and everywhere. He was someone you just wanted to stay away from.'

And people did just that. Ryan would therefore occasionally be seen in local pubs standing alone, drinking a pint or two of beer before leaving. Peter Bullock, the landlord of the Red House at Marsh Benham, between Hungerford and Newbury, recalls his surly, solitary presence in his pub: T can remember Ryan standing at the bar or sitting at a table. One thing never changed: he was always alone. I don't think that he was a loner by choice, mind you -just that he seemed inadequate.'

Ryan certainly considered his own height of five foot six inadequate. Nor was he very impressed with his head of hair, for he worried a great deal about its premature loss. In fact Ryan was something of a worrier all round, and his doctor was in no doubt that the recurrent lump in his throat which troubled him so was caused simply by nervous stress. His other features were nothing unusual: a beer gut, short light brown hair and a light beard to match.

As a youth Ryan was so reserved and awkward that his headmaster, David Lee, struggles to remember his former pupil: 'He was unremarkable, an anonymous sort of lad really, who failed to distinguish himself either academically or in sports.' Years later a contrived anonymity would continue, with Ryan sporting sunglasses in all weathers, an absence of sunshine not deterring him one iota. Being tough, or being seen to be tough, was certainly important to him. And it was no doubt the feeling of power over youngsters which prompted him once to take a job as a bouncer at local rock concerts. Ryan's new role, with his gun tucked out of sight, neatly matched the image he had developed.

Not surprisingly, Ryan was not much of a hit with women. 'In all the time I knew him,' Gary Devlin recalls, 'I never once saw him with a girlfriend. He was into his guns and kept himself occupied with that.' This is not to imply that Ryan's sexual preference inclined towards men or boys, for it did not. It was just that he was entirely lacking in the social skills which might have led to a sexual relationship. In fact in June 1987 Ryan made such a nuisance of himself at a party by persistently asking a local waitress to go out with him, and refusing to take no for an answer, that he had to be warned off by her friends. And Michael Ryan did not like to be warned off. Not one bit.

By contrast, there was no risk of his being rejected by Blackie, his labrador, whom he loved deeply and looked after very well. Ryan would often be seen out walking Blackie. If anyone crossed his path, or his crossed theirs, then providing that person was not one of the neighbours with whom he had fallen out because of his shooting activities, then invariably his greeting was both courteous and friendly. 'Hello, all right?' he would always ask. Sometimes he would stop and talk knowledgeably to the local children about the latest television film he had seen or video he had hired.

If Michael Ryan was nondescript, so too was his home. The li

ving-room was decorated with a heavy, old-fashioned wallpaper of a golden hue. Past the kitchen was a glass lean-to, which his father had built and his mother used as a utility room. Beyond that was the garden, some 200 feet long and complete with a garage and a greenhouse. Michael's room was at the front of the house on the first floor, overlooking the street, which was really a lane, with houses on one side and Hungerford Primary School on the other. This house was the constant backcloth to Michael Ryan's rather dreary and joyless life. It was here that he had been brought, as the only child of his parents, when he was just a few days old.

Dorothy Ryan was a grafter. And invariably she was grafting for her son. She paid for everything: the fast cars, the best clothes and the latest records. She always had, and what is more she was happy to have done so. This suited Michael down to the ground, for while his mother was happy to give, he was happy to take. Her money, however, was hard-earned, as she worked as a dinner lady at Hungerford Primary School. The timing of her job enabled Dorothy to have a couple of hours off before starting work again as a silver-service waitress at the stylish Elcot Park Hotel at Kintbury, on the outskirts of Hungerford. Here she had felt privileged to serve members of the Royal family on more than one occasion. If guns made Michael happy, therein lay Dorothy's satisfaction too. That explained why she was more than happy to pop across the road every week to pick up her son's pile of survival and gun magazines.

Relatives and friends could see all too clearly that Dorothy Ryan, who, unlike her son, was extremely popular in the neighbourhood, was pampering Michael to a degree which defied description. Michael could be a polite and well-mannered young man, but he was at times a sullen, brooding character, and prone to extreme mood swings. He was often rude and abusive towards his mother. The analysis was hardly complicated: he had been thoroughly spoiled. Aunt Constance Ryan, however, is a little more charitable in her assessment: 'Actually we got on rather well. We shared similar tastes in music and it seemed as if there was not that much of an age difference between us. He was a very, very nice person. But he was also a rather sad and lonely boy. It didn't seem as if he had many friends.'

In 1984, aged eighty-one, Ryan's father, Alfred, had died. It was the end of a long battle against cancer. At first Ryan took the death of his father badly, sinking into a depression, and he turned to his doctor for advice and support. According to Leslie Ryan, his uncle, it was a terrible blow for the young man: 'His father, who he called Buck, was his life. When he went, something in Michael seemed to go too.'

This might have been true in the first stages of Ryan's grief, but it was certainly not for long, according to his cousin, David Fair-brass: 'Michael was quite articulate, but a man of few words. I had known him all of my life and you wouldn't think there was anything strange about him. I only met him with the family, not socially, and he used to drop my auntie down to visit. I never saw his guns, but at his father's funeral he showed me his collection of antique swords. After his father died, Michael became more outgoing if anything. Alfred was quite a disciplinarian, but Michael used to look up to him. Before Alfred's death, Michael was shy, introverted and insecure. But the change that came over him after his father had died was incredible. We could see him coming out of himself. We were all quite pleased for him at the time. And when we heard about Michael's forthcoming marriage we were all very excited indeed. But we never did meet her or hear any name mentioned.'

There was a single compelling reason why David Fairbrass was never to meet this fiancée: she was but a figment of his cousin's imagination. Ryan might well have made some progress since the death of his father in terms of the development of his own personality. Yet the fact remained that he was an outsider, a loner, a nobody whose life was so full of rejection and failure that he chose what appeared to him to be a rather satisfactory solution. This was to concoct an altogether more fanciful, successful and dynamic existence which he knew he would never be able to achieve in reality. While his everyday life might have been humdrum, Ryan's fantasy Ufe could hardly have been more colourful.

Witness Ryan's bizarre invention of a relationship with a ninety-five-year-old retired colonel. Mrs Eileen North, Dorothy Ryan's closest friend, recounts the story of this elaborate fiction: 'I worked as a school-dinner lady with Dorothy and my own mother lived next door to the Ryan family. I suppose you could say that, relatives apart, I knew the family better than anyone else. Mrs Ryan was devoted to her son and it was she who told people how Michael had become friendly with this colonel who employed a nurse and housekeeper. Michael claimed he was going to fly to India because he had been invited to his tea-plantation there, but that the flight had had to be cancelled due to a bad storm. He was also supposed to be paying for flying lessons for Michael. He was supposed to be the owner of a hotel in Eastbourne, although he himself lived in Cold Ash. Not only was he intent on leaving Michael his fortune, he was also due to inherit a five-bedroomed house. Michael also told people that he was engaged to the colonel's nurse, but that the wedding was postponed after she had fallen from a horse. Then the wedding was called off when she refused to buy Mrs Ryan a birthday present. Oh yes, and this colonel person was also meant to be buying Michael a Porsche, Ferrari or Range Rover.'

The story Ryan spun to Edred Gwilliam, a dealer in antique firearms, concerned not an ageing colonel but a young Irish girl. Others were to hear this tale too. Ryan claimed that he had been married to an Irish girl who had borne his child, but that the marriage had run into difficulties after he had caught his wife in bed with an elderly uncle for whom he had once worked. His estranged wife, he told Gwilliam and workmates alike, had returned to Ireland with the child. In any event, Ryan explained, the relationship between the Irish girl and her mother-in-law had always been a troubled one. Ryan's hard-luck story had not ended there, for after the death of his father he had been left a lot of money and he and a partner were in business together, renovating properties in London. At one stage, Ryan insisted they had ten or twelve men working for them but his partner had run away to Australia and left him bankrupt.

Dorothy Ryan had certainly believed her son when he had spoken of the colonel from Cold Ash. It was she, after all, who had picked up the telephone to the Fairbrass family in Calne, twenty-five miles from Hungerford, proudly inviting her relatives to Michael's wedding. Edred Gwilliam had likewise believed his cus- tomer, who had, after all, bought a pair of Queen Anne pistols, a holster pistol and an antique naval sword from him over the years and had given him no reason to disbelieve what he said. Nor was there any shortage of additional fantasy. Other tall stories retailed by Ryan included his claims that he had once run a gun shop or antique store in Marlborough; that he had held a private pilot's licence; that he had served with the 2nd Parachute Regiment; and that in 1987 he had taken a trip to Venice on the Orient Express. Every story was devoid of the slightest trace of truth. But wherever Michael Ryan went two things now accompanied him: firearms and fantasies.

Ryan had left school in 1976, just after his sixteenth birthday, without a single qualification. For almost a decade he had drifted aimlessly from one unskilled job to another, with intermittent periods on the dole. He was a great disappointment to his father, who had hoped for better things.

When Ryan did work, however, his style was at least memorable. He once found a job as a handyman at Downe House Girls School in Cold Ash, near Newbury, the town where the fictitious colonel was supposed to have lived. But Fred Haynes, the school's gardener, remembers Ryan's four months' labour there for one reason only: 'He once shot a green woodpecker, which the rest of us found very offensive.'

Between November 1985 and Easter 1986 the gun enthusiast worked as a labourer at nearby Littlecote, the home of the multimillionaire businessman Peter de Savary. Although the great hall at Littlecote was decorated with well over a hundred guns dating from the Civil War, Ryan apparently failed to show any interest in the collection. Littlecote's project director, John Taylor, whose task it was to oversee the £6-million conversion of s

tately home into historic theme park, remembers Ryan only for being 'terribly overmothered'. Eddy Pett, also involved in the project, summed up Ryan's personality neatly: 'Michael Ryan seemed a very nice chap to me. He was pleasant enough, but he appeared to be someone who wasn't getting to grips with life.'

Pett was right: nothing seemed to be working out for Ryan. But then things had never really gone his way. The job at Littlecote lasted for only six months, after which Ryan resumed a path that had long been familiar: back to the dole office. Then, in April 1987, after a year out of work, Ryan thought that he might have fallen on his feet. The Manpower Services Commission was advertising for people to work on an environmental improvement project. Sponsoring this programme was Newbury District Council, which appointed John Gregory as the scheme's manager. One requirement was that applicants had to have been out of work for over a year, a criterion which Ryan was able to fulfil. Ryan knew that the job was poorly paid, at £64 per week, but after a prolonged spell of unemployment he was happy to be back in work. A week after his interview he was working again, this time clearing footpaths and mending fences. At first all seemed to go well and Gregory had no cause to complain: 'Michael Ryan was a good worker, a conscientious worker - and he certainly pulled his weight. Although he was very quiet, he was also well-spoken and well-behaved. I got the impression that he enjoyed working outdoors.'

But Charles Armor got to know Ryan rather better, for he was directly responsible for supervising his work on the project, along with some forty-five other men: 'He was sullen and a bit moody really, but he joined in the conversations with the lads. He would take the mickey out of the chaps, but he did not like it if they took the mickey out of him.'

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre

Hungerford: One Man's Massacre